Pierre de Ronsard Rose (Photo credit: Jamain (2011), Wikipedia)

Pierre de Ronsard Rose (Photo credit: Jamain (2011), Wikipedia)

‘Pierre de Ronsard‘, also known as ‘Eden Rose‘ is a beautiful rose bred by Jacques Mouchotte before 1985. On the 400th death anniversary of the great French poet, Pierre de Ronsard, in 1985, this rose was introduced in France by Meilland International as ‘Pierre de Ronsard’. Cupped and globular blooms are characteristically old-fashioned and moderately fragrant. Large creamy flowers with carmine-pink edges are borne mostly solitary, turn pink when aging. This rose is robust with healthy dark green foliage and produces blooms prolifically throughout the season. Pierre de Ronsard is one of the most beautiful roses and named after a great French poet.

Manoir de la Possonnière, Ronsard’s home (Sourced from Wikipedia)

Manoir de la Possonnière, Ronsard’s home (Sourced from Wikipedia)

Pierre de Ronsard was born on 11th September 1524 in La Possonnière, in the village of Couture-sur-Loir (present-day Loir-et-Cher) as the youngest son of Loys de Ronsard. His family was noble but a poverty-stricken. He was educated at home in his earliest years and sent to the Collège de Navarre in Paris at the age of nine.

In 1533, Ronsard left his home to receive formal education in Paris at the academically and religiously conservative Collège de Navarre. In spring 1534, after only one semester of study, the boy was withdrawn from the school and returned home. This departure was both due to the young Ronsard’s homesickness and to his father’s fear that his son might become associated with the position taken by the college against the reformist leanings of the king’s sister, Marguerite de Navarre.

Madeleine de Valois (1520-1536)

He entered the service of the royal family as a page in 1536 and accompanied Princess Madeleine of France after her marriage James V of Scotland. On July 2, 1537, barely a month and a half after arriving in Scotland, Ronsard watched ravaging effects of tuberculosis, a highly contagious and often deadly disease, taking the lady’s life before she reached her seventeenth birthday. These encounters with human mortality at an early age account had a profound effect on Ronsard and reflected that on his poetry. One year after the death of the queen, Ronsard returned to France.

A diplomatic career opened to him and he travelled overseas in many diplomatic missions. During his travels abroad, Ronsard learnt to speak English. Ronsard’s life took a different path after his return to France in August 1540, he was struck by a high fever that permanently impaired his hearing. He had to abandon his pursuit for a military career and retreat to La Possonnière.

Ronsard was strongly influenced by his relationship with his cleric uncle, Jean de Ronsard who was a writer of verses. He played an important role in his nephew’s earliest education. The three-year convalescence afforded him an opportunity to deepen his admiration for the natural beauty of the French countryside and to peruse his uncle Jean’s library. The result was an awakening to his inner calling, a discovery that led to his decision to write.

The church provided the only future for someone in his position, and he accordingly took minor orders. In March 1543, Ronsard shaved his head in the manner of those entering the priesthood. He was never an ordained priest, but it permitted him to receive an income from certain religious posts. With the deaths of his father in June 1544 and his mother in January 1545, Ronsard devoted time on his poetic ambitions.

Ronsard studied literature for seven years in the Collège Coqueret. During this period, he studied the classics, learnt Greek, read all the Greek and Latin poetry and gained some familiarity with Italian poetry too. With a group of fellow students, he formed a literary school, known as La Pléiade, with an aim to produce French poetry that would stand in comparison with the verse of classical antiquity.

Cover Page Photo of the Frensh Edition of Les Amours de Ronsard (2017)

Cover Page Photo of the Frensh Edition of Les Amours de Ronsard (2017)

In January 1550, the twenty-five-year-old Ronsard published his first major work, The Odes of Pierre Ronsard (1550). Amours de Cassandre, which is the 5th book of Odes, in 1552, was dedicated to the 15-year-old Cassandre Salviati (1530 – 1607), a daughter of an Italian banker, whom Ronsard met at a court ball in 1545, when he was twenty and she was fifteen. As a man of the church, Ronsard was unable to marry; but it didn’t stop him falling in love with her. Some believe the attributions to ‘Cassandre’, as a generic name, for the loved woman. According to Ronsard’s first biographer, Binet, who knew him personally towards the end of his life, Ronsard fell in love more with the name ‘Cassandre’, full of tragic and epic connotations, than with the woman.

Les Amours de Cassandre: XX

I’d like to turn the deepest of yellows,

Falling, drop by drop, in a golden shower,

Into her lap, my lovely Cassandra’s,

As sleep is stealing over her brow.

Then I’d like to be a bull, white as snow,

Transforming myself, for carrying her,

In April, when, through meadows so tender,

A flower, through a thousand flowers, she goes.

I’d like then, the better to ease my pain,

To be Narcissus, and she a fountain,

Where I’d swim all night, at my pleasure:

And I’d like it, too, if Aurora would never

Light day again, or wake me ever,

So that this night could last forever.

The Bocage (“Grove”) of poetry of 1554 and in the Meslanges (“Miscellany”) of the same year, contain some of his most exquisite nature poems with a description of solitary wanderings of a child in the woods.

Marie de Clèves (1553-1574)

Marie de Clèves (1553-1574)

In Les Amours de Marie his poems were addressed to a country girl, Marie, who was the youngest daughter of Étienne Guyet, a minor noble. Though she did not return Ronsard’s love and married another, her early death in the early 1570s brought a wonderful series of sonnets from Ronsard, more sombre in tone than the first part of the book but balancing it in their elegance. Some believe, Marie was the mistress of the Duke of Anjou. Marie de Clèves died in 1574.

Sur La Mort de Marie: IV

As in May month, on its stem we see the rose

In its sweet youthfulness, in its freshest flower,

Making the heavens jealous with living colour,

Dawn sprinkles it with tears in the morning glow:

Grace lies in all its petals, and love, I know,

Scenting the trees and scenting the garden’s bower,

But, assaulted by scorching heat or a shower,

Languishing, it dies, and petals on petals flow.

So in your freshness, so in all your first newness,

When earth and heaven both honoured your loveliness,

The Fates destroyed you, and you are but dust below.

Accept my tears and my sorrow for obsequies,

This bowl of milk, this basket of flowers from me,

So living and dead your body will still be rose.

Ronsard’s popularity was overwhelming, and his prosperity was unbroken during the period of 1550 and 1560s. Even the rapid change of sovereigns did Ronsard no harm. Though Ronsard continued writing, he returned to the court in the 1560s, serving Charles IX and Marguerite. In addition to filling his duties as a royal poet, Ronsard was able to publish new versions of his existing collections, revising old poems, and adding new pieces.

Hélène de Surgères

Hélène de Surgères

In 1578 he published a collection of sonnets, the Sonnets for Hélène. By contrast with the earlier love affairs, this one with Hélène is a ‘courtly’ love although Hélène herself was real. Hélène de Surgères was a daughter of a courtier. It is open to debate how much any of these poetic collections reflect real love affairs of Ronsard. The poetries were written over a longer period and is more laden with the traditions than the genuine experience of love.

Sonnets Pour Helene Book I: XIX

So often forging peace, so often fighting,

So often breaking up, and then re-forming,

So often blaming Love, so often praising,

So often searching out, so often fleeing,

So often hiding ourselves, so often revealing,

So often under the yoke, so often freeing,

Making our promises and then retracting,

Are signs that Love strikes at our very being.

A sign of love is this loving inconstancy.

If in a moment feeling both hate and pity,

Vowing, un-vowing, oaths sworn and un-sworn,

Hoping that’s hopeless, comfort that’s comfortless,

Are true love signs, then our love’s of the best,

Since we are always at peace, or at war.

Pierre de Ronsard Rose (1985)

Pierre de Ronsard Rose (1985)

Sonnets Pour Helene Book II: XLIII

When you are truly old, beside the evening candle,

Sitting by the fire, winding wool and spinning,

Murmuring my verses, you’ll marvel then, in saying,

‘Long ago, Ronsard sang me, when I was beautiful.’

There’ll be no serving-girl of yours, who hears it all,

Even if, tired from toil, she’s already drowsing,

Fails to rouse at the sound of my name’s echoing,

And blesses your name, then, with praise immortal.

I’ll be under the earth, a boneless phantom,

At rest in the myrtle groves of the dark kingdom:

You’ll be an old woman hunched over the fire,

Regretting my love for you, your fierce disdain,

So live, believe me: don’t wait for another day,

Gather them now the roses of life, and desire.

Although some critics found an appealingly exaggerated quality in some of his poems, during his lifetime, Ronsard’s work received an incredibly positive reaction from his contemporaries.

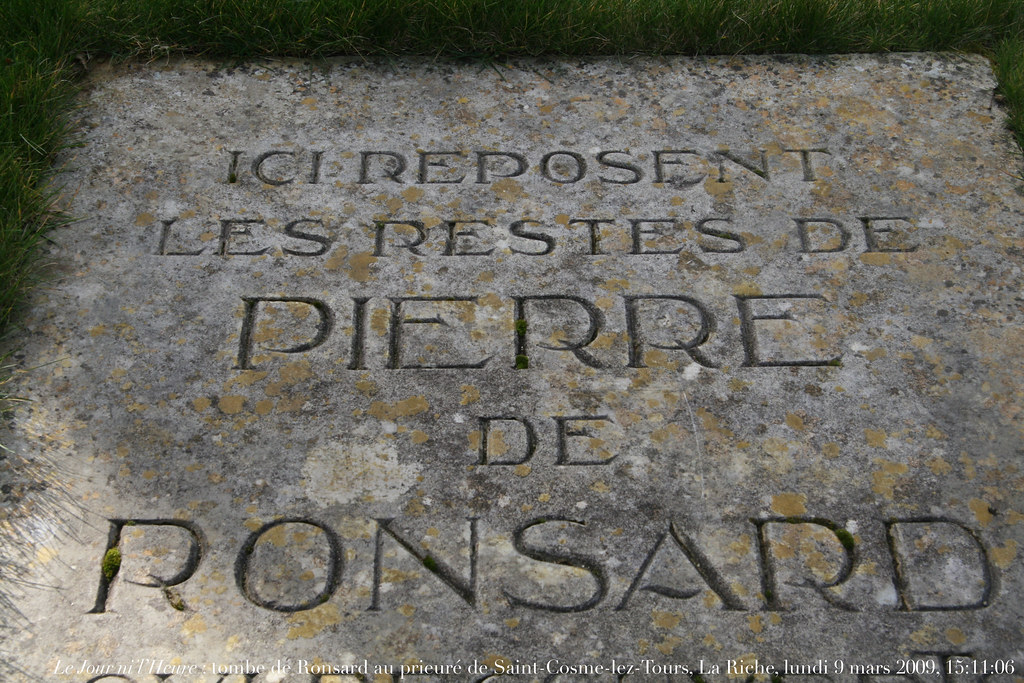

His last years were saddened not only by the death of many of his closest friends, but by increasing ill health. However, this did not interfere with the quality of his literary work and some of his final verse is among his best. Towards the end of 1585 his health deteriorated. He seemed to have moved restlessly from one of his houses to another. When the end came—which, though in great pain, he met in a resolute and religious manner. He was at his priory of Saint-Cosme in Touraine, and he was buried in the church of that name on Friday, 27 December 1585.

PS: All the photos are sourced from Wikipedia under Creative Commons license.

References:

Armstrong, A. E. (n.d.) Pierre de Ronsard. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Pierre-de-Ronsard

Encyclopedia (2020). Pierre de Ronsard. Accessed from https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/literature-and-arts/french-literature-biographies/pierre-de-ronsard

My Poetic Side (n.d.) Pierre de Ronsard Poems. Accessed from https://mypoeticside.com/poets/pierre-de-ronsard-poems

Poetry in Translation (n.d.). Pierre de Ronsard: Selected Poems. Accessed from https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/French/Ronsard.php#anchor_Toc69989214

Wikipedia (n.d.) Pierre de Ronsard. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_de_Ronsard

Pierre de Ronsard Rose (Photo credit: Jamain (2011), Wikipedia)

Pierre de Ronsard Rose (Photo credit: Jamain (2011), Wikipedia) Manoir de la Possonnière, Ronsard’s home (Sourced from Wikipedia)

Manoir de la Possonnière, Ronsard’s home (Sourced from Wikipedia)

Cover Page Photo of the Frensh Edition of

Cover Page Photo of the Frensh Edition of  Marie de Clèves (1553-1574)

Marie de Clèves (1553-1574) Hélène de Surgères

Hélène de Surgères Pierre de Ronsard Rose (1985)

Pierre de Ronsard Rose (1985)

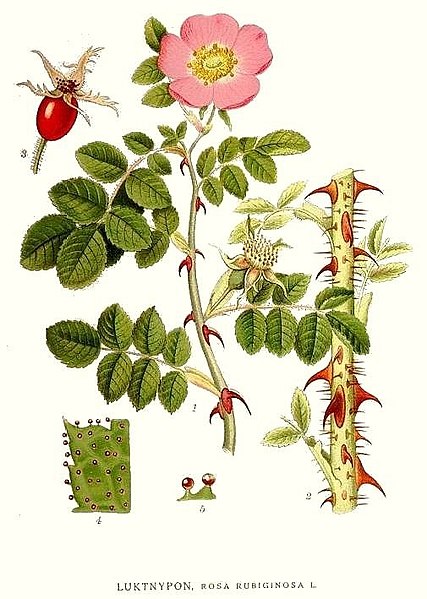

Sweet-Briar Rose (Photo credit : Andrew Coombes)

Sweet-Briar Rose (Photo credit : Andrew Coombes) Botanical Drawing of Sweet-Briar Rose (By C. A. M. Lindman (1856–1928))

Botanical Drawing of Sweet-Briar Rose (By C. A. M. Lindman (1856–1928))